TRIP TO QATAR

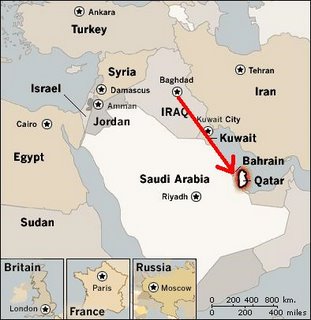

Not long ago, I took a trip to Qatar to attend an anti-terrorism course. Qatar is also the place where the military sends troops on 4-day R&R (“rest and relaxation”) trips. For a couple of years now, the military in Iraq has been sending troops down there to take a break from the rigors of life in a combat zone. So when I was told I was being sent to Doha, Qatar, I didn’t complain.

I hopped on a helicopter to Baghdad to spend the night, and the next day I boarded a huge C-5 Galaxy troop transport plane and flew to Qatar. As I was quickly finding out, however, nothing in this part of the world happens the way it is supposed to. The 2-hour plane trip I envisioned when I pulled out a map turned into nearly a 12-hour ride, full of delays, mechanical breakdowns, and stiff-necked cat-naps in the hot plane.

Finally we touched down early on a Sunday morning at the airbase in Doha. I was so exhausted from the trip that everything seemed blurry. I checked in my pistol at the airport, and waited around with the other soldiers and Marines for our ride. It was about 4 in the morning. Some guys crashed on the benches like vagrants. For me, it was a standard coffee scenario. Gradually the world clarified itself, and I began to chat with some of the other guys. They were from all over Iraq, and most of them were in charge of base security and force protection, like I was. Eventually we were picked up by a couple soldiers driving Toyota Landcruisers. It was just barely getting light out by the time we careened onto the freeway that stretched between the airbase and the base that our classes would be held at. The soldiers drove down the road like maniacs into the rising sun. Partly because they could, and partly because that's how you drive on a freeway in Doha. It took about 20 minutes to get to the other base. The security at the base was extremely tight, so it took us a little while before we finally got into the base and checked into our barracks room.

We would be living in a large warehouse for the week. Inside the warehouse are row after row of buildings and trailers that are full of barracks rooms. The rooms are large, and lined with bunk beds on both sides. I pulled my two bags into the room. It was already full of snoring soldiers and Marines that had pulled in several hours before us. As any military guy knows, that means that all of the good beds are gone. So I found an empty top bunk, kicked off my boots, and slept deeply for 10 hours.

That afternoon, I took a shower and changed into shorts and a t-shirt. I took a long walk around the base. It was still hotter than hell outside; much hotter than in Iraq in May. In Qatar it was already 120. The base actually didn’t have much more than some of the big bases in Iraq. There was a Burger King, a large PX (a glorified convenience store), and bunch of recreation centers. Granted, the stuff in Qatar was nicer. The pool had a Chili’s restaurant next to it. The gym served smoothies. It was a nice place to hang out for a couple of days. But in reality, the only tangible thing that separated it from Iraq was that you could drink beer there. Three beers a day. Just enough beer to make you wish you could drink another one and be pissed off that you couldn’t.

That night I wrote in my journal:

On an intellectual level I understand the appeal of this place. But in reality the only appeal is 3 beers a day. A barren desert. Oil wells and mirrored buildings. Mercedes Benzes. Tacky sunglasses. Huge U.S. bases, double fences, coiled razor wire, ditches, trenches, thickly veined contractors’ arms, tacky sunglasses, and mirrors under your car. Soldiers and sailors. Four days of rest. Do-rags, earrings, halter tops, condoms in the PX but no place to go. Join the Navy and see the desert. Wear cool sunglasses. It’s not just a job, it’s like being a choir boy. (Oh, and you also might die a very violent death.) But sorry, no more than three beers, please. We wouldn’t want to offend the people that we’re paying gazillions of dollars to here, now would we? And we certainly wouldn’t want the soldiers to have too much fun.

During the Vietnam War, soldiers could take R&R in Bangkok, or even Saigon, for that matter. Well Doha is this war's Saigon. And let me tell you, Doha... I've been to Saigon. I've walked and drank beer in Saigon. Saigon was a friend of mine. You, Doha, are no Saigon.

If soldiers go to Qatar on R&R, they have the chance to take a fishing trip or a tour of the souks (markets). But since the group I was in was taking a class, we weren’t able to go into town at all. It was a really raw deal. I’ve been in countries that are far more dangerous than Qatar, yet I was told I needed an escort to go into town. I suppose, in the end, I could have found a way out there, but since I was in class most of the day, it really wasn’t worth the effort. If I go back there again while I’m in Iraq, I’ll certainly go out there. I just want to get a few souvenirs—maybe some local handicrafts. Buying souvenirs from the bazaar on base is like buying trinkets at an airport and acting like you’ve been to the city. Having an “I Heart NY” coffee cup you got at Kennedy Airport doesn’t make you a world traveler. Anyway, it seems that most of the crap on the bases in Iraq and in the Middle East is all made in Pakistan or Turkey. The same stuff I saw in Western China. Stuffed camels. Ugly dolls. Wooden Harley Davidson motorcycles. As I said, crap. I can’t believe people put some of these things in their houses. What do you do with a big plastic palm tree on a plate that says “Doha, Qatar” on it? With no sites to see, I mostly just lifted weights and then hung out with a few of the Marines that were taking the classes with me. We played pool, shot the shit, threw darts. Nursed our three beers. If you’ve managed to dehydrate yourself enough, three 16.5 oz beers is enough to make you fall asleep quickly at night while you’re reading in the dark.

* * *

We get used to our surroundings in Iraq. Sometimes things that seem interesting to folks back home don’t even get a second glance from us. But I am trying to stay alert; trying to record things in my head that I can remember later on. Remember to tell my Marines when I get home. Remember to tell my children. And I suppose I need to start writing these things down. These stories. I’ve always been a reader. I’ve always loved war stories. Even before coming into the Marine Corps, I read things like The Things They Carried or With the Old Breed. I know already what all men that have gone to war know—namely, that war, when boiled down to the hard truth on the ground, is nothing more than the slaughter of young men in the prime of their youth. Some of them, before they’ve even had a girlfriend. Before they’ve even done things in life that they will regret. Some of them, with a wife and young children. But now I’m here in the middle of it. Hearing young men tell you about the dangers they face every day, you’d think that it’s just a part of their job; something they have to put up with, like the long commute into San Francisco. But I guess it’s just the way we deal with it—mortician’s humor. Some of it is also the fact that by talking about it, we teach others. We keep ourselves aware. In the end, it’s a survival mechanism.

But telling the stories is important. Some day when I’m old and full of sleep, the war will be a distant memory. I don’t want what happened here to be forgotten. I don’t want it to be a footnote. So I’m going to start to write down the things that I hear. A lot of it is ugly. But it’s true.

One night I saw a couple of young military guys in the pool hall on the base walking toward me. At first I thought they were drunk, but they were actually just horsing around while they were walking. Just being kids. One of them saw me with my USMC shirt on, and they walked up to me and asked if I was a Marine. “Yes,” I said. I told them where I was stationed. One was an Air Force kid; one was a Marine from 3/5. He had been wounded by an IED strike (basically, a hidden bomb on the roadside) about two weeks before. He only had been hit in the arm, but he had been sent to Qatar to recuperate. He was so happy to see another Marine. Just a young kid, maybe 19, but he looked much younger to me. Skinny kid. A killer. He told me that before the IED hit, he had had a sick feeling in his stomach. “I’ve been on all kinds of convoys, Sir, but I never felt like that before. They had me in the back of the highback HMMWV. It was dark out, and I was tired, riding in the back.” He paused and shook his head, looking me straight in the eye. “I just pressed myself up against the back of the vehicle. I don’t know what it was, Sir… I just knew something was going to happen that night. When it blew up, I had fallen asleep. Right away I knew what happened. There was just smoke and dust everywhere. Luckily nobody got really hurt. But for a minute, I was just wondering if I was OK. It was a lot of confusion.” I looked down at the bandages on his skinny but strong and veiny arm. “Just an arm wound, Sir. But all I could think about right after the blast was my wife and 5-month old son.”

Many of you back home think that the people fighting this war are hardened men; strong and determined soldiers with lines on their faces. In the pictures, they are gritty and tired and dirty. Smoking cigarettes and turning wrenches. Get that GI Joe and Hollywood crap out of your head. As I watched that young Marine walk off to buy an ice cream and sign up for a fishing trip the next day, I saw what I already knew and what I can tell you now: kids fight our wars. That’s not a judgment on this or any other war. Just an interesting fact that's as true now as it has always been.

I met a lot of good guys in Qatar. Since we shared the common culture of the Marine Corps, after a few days, it seemed like some of us had known each other for years. Our paths ran alongside each other for a few days, and then we all moved on, back to our piece of this war.

Sometimes I look at old war photographs from World War II, and I stare at the faces of the men. I’ve always thought that they looked like such great guys. They’re smiling; joking. Hard-nosed Italian kids from NY. Carefree Californians. South Boston Irish toughies. I wonder if my kids will look at my old pictures and think the same thing. If they ever ask me about the guys I met over here, I’ll tell them, yes, the men in the pictures were good dudes. Many of them never came back from that desert, and we can’t ever forget it. I’ll say that they were the best men our country had in those years.

Sometimes I look at old war photographs from World War II, and I stare at the faces of the men. I’ve always thought that they looked like such great guys. They’re smiling; joking. Hard-nosed Italian kids from NY. Carefree Californians. South Boston Irish toughies. I wonder if my kids will look at my old pictures and think the same thing. If they ever ask me about the guys I met over here, I’ll tell them, yes, the men in the pictures were good dudes. Many of them never came back from that desert, and we can’t ever forget it. I’ll say that they were the best men our country had in those years.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home